A thin, dog-eared paperback graced our kitchen’s bookshelf from the time I was just about old enough to see above the counter. To my child’s eyes, its title, “Diet for a Small Planet,” seemed welcoming: I was a small person, so what could be bad about a small planet?

Frances Moore Lappé’s first book, “Diet for a Small Planet,” was published in 1971, based on her research on the merits of a plant-centered diet, with non-meat proteins.

(Michael Piazza)

Indeed, author Frances Moore Lappé is the first to say that her book, and the 50 years of work focused on the intersection of food and democracy that has followed, is about hope. “I’m not an optimist — I’m a possible-ist,” she says. “Everything is possible, we just have to make it happen.”

Less a cookbook than a dissertation, the original book, published in 1971, featured recipes in the back that fascinated me, with such names as Tiger’s Candy, Feijoada and Peanut Butter Cookies With a Difference. But the bulk of the book was focused on Lappé’s deep concern that our small — by which she meant interconnected — planet was failing to meet the most fundamental needs of its inhabitants: keeping people fed with healthy foods.

It was a concern that began when she was a young social worker in some of Philadelphia’s most impoverished neighborhoods in the mid-1960s. “I was going door to door, talking with women who were simply desperate to feed their children,” she recalls in a phone interview from her home in Belmont, Mass. But the lightbulb didn’t go off until a couple of years later, after Lappé had access to the library stacks at the University of California Berkeley, where her husband was doing his postdoctoral work.

Intrigued by such books as Rachel Carson’s “Silent Spring” (1962) and Paul Ehrlich’s “The Population Bomb” (1968), Lappé’s own research led her to what felt like an obvious conclusion: “I thought, food is the most basic thing,” she says. “Everybody needs to eat, and it’s easy to calculate how much we need. We can measure it, and we can measure health from it.”

At its heart, “Diet for a Small Planet” holds that universal access to a healthy and sustainable diet provides a global springboard to a better environment, functional democracies, stronger economies and increased social justice. While the concept might seem commonplace today, it was revolutionary at the time. For Lappé, now 77, focusing her research on the merits of a plant-centered diet was inevitable, even though she was not herself a vegetarian at that time, because it was clear that growing legumes for consumption was more cost-effective and eco-conscious than raising animals for food. What she didn’t expect was that her research would catch the eye of Betty Ballantine, co-owner of Ballantine Books, a popular paperback publisher.

Ballantine’s instincts that Lappé’s ideas would capture the attention of a nation were correct. Lappé says, “I once asked Betty, ‘Why did you take a chance on me?’ I’d never written a book before, and she said, ‘If you couldn’t write it, I could do that. It was the ideas I loved.’ And because she took that chance, my life was transformed.”

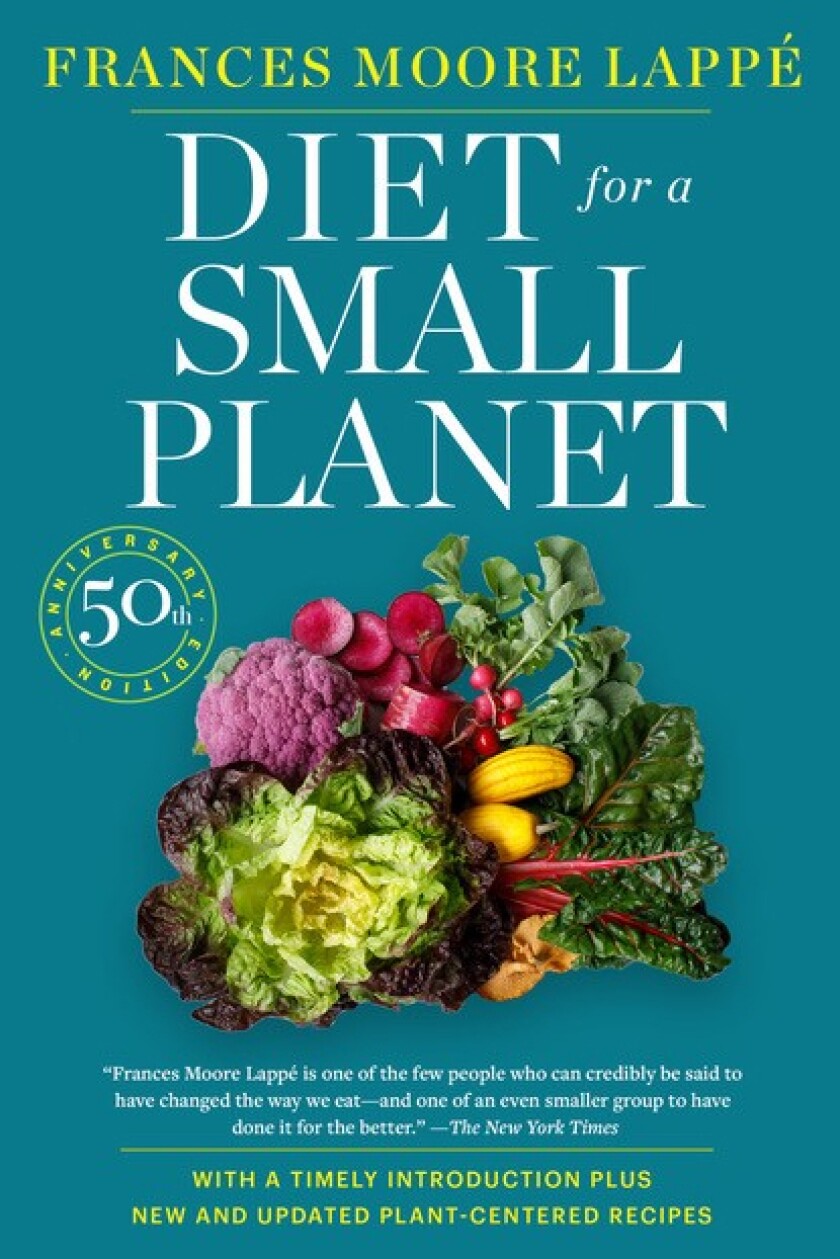

The 50th edition of Frances Moore Lappé’s book contains more recipes from Black, Indigenous and people of color and updates those in the original edition.

(Manahl Marielle)

Some 3.5 million copies later and with 10th, 20th and, now, 50th anniversary editions published, the unexpected food revolution spawned by “Diet for a Small Planet” has undoubtedly influenced the farm-to-table movement, community-supported agriculture, organic farming practices and the plant-based industry.

Michael Pollan, the author of the hugely influential 2006 book “The Omnivore’s Dilemma,” calls Lappé’s work “one of the most visionary books of the last 50 years.”

“Long before anyone recognized the environmental impact, and sheer inefficiency, of using cows to produce protein, Francis Moore Lappé told us what was at stake when we eat beef,” he said in an email. “And now that the links between meat production and climate change are understood, her book seems more prophetic than ever.”

Anna Lappé was inspired by and is following in her mother’s work.

(Clark Patrick)

“Diet for a Small Planet” also influenced Lappé’s daughter, Anna Lappé, born two years after the original book was published. Growing up along with her older brother, Anthony, with the daily impact of their mother’s work reflected in their home kitchen — as well as in family global travels in pursuit of more research — led Anna to become passionate about food justice and work alongside her mother on issues of sustainability.

“When I think back on my most vibrant childhood memories,” says Anna, now 48, “a lot of them were literally in the streets, because my mother’s life’s work was always this interweaving of food with this very political message, that we have to talk about democracy and power if we want to talk about what’s on our plates being good for our bodies and the planet.”

“If you look at all the ancestral cuisines around the world, they are all fundamentally healthy. It’s not helpful, nor is it accurate, to uplift the Mediterranean diet as the only healthy option.”

Anna Lappé

Anna’s own deep dive into the connection between the climate crisis and big agriculture resulted in “Diet for a Hot Planet” (Bloomsbury, 2010), adding another focus to her mother’s original work. But it was with the 50th anniversary edition of “Diet for a Small Planet” that Anna took on a specific goal of adding more recipes from Black, Indigenous and people of color and taking a serious look — with the expert help of nutritionist Wendy Lopez — at both culling and updating the recipes from the original edition. Ingredients such as soy flour and margarine and ideas such as “protein combining” (designed to alleviate the fears of skeptics of vegetarian diets) from the original book were scrapped, while the overall focus continues to stay on eating whole fruits and vegetables.

“One of the things that I hope comes out of the revised book is what is healthy food, what is a plant-centered diet,” Anna said in a phone interview from her home in Berkeley. “It is not the prescription of one specific diet. If you look at all the ancestral cuisines around the world, they are all fundamentally healthy. It’s not helpful, nor is it accurate, to uplift the Mediterranean diet as the only healthy option.”

“Diet for a Small Planet,” 50th anniversary edition by Frances Moore Lappé (Penguin Random House; 512 pages)

(Penguin Random House)

With those goals in mind, the new edition includes vegetable-forward recipes from a number of new contributors representing food cultures found around the globe, including Padma Lakshmi’s Yellow Velvet Lentil Soup With Cumin and Dried Plums, Sean Sherman’s Roasted Corn With Wild Greens Pesto, Yasmin Khan’s Eggplant and Feta Kefte, and Bryant Terry’s Slow-Braised Mustard Greens.

“I really wanted to include other people into the mix,” Anna says. “They really reflect our food values in terms of seeking out food that is good for the planet and also being very involved in the social justice aspect of food issues.”

The Sopa de Milpa recipe contributed by Luz Calvo and Catriona Rueda Esquibel, from their book “Decolonize Your Diet: Plant-Based Mexican-American Recipes for Health and Healing” (Arsenal Pulp Press, 2015), is just one example of the Lappés’ focus on expanding the message of “Diet for a Small Planet” a half-century later.

“I read the original book probably in 1976, when I was in high school,” says Calvo, “and it had a huge impact on me and my thinking and my diet at the time. We’re coming from a Mexican American perspective of communities that have long had sustainable food practices that have perhaps not always been recognized. There’s definitely a new generation of readers that can be brought into the conversation, and what’s beautiful about the book is recognizing that this is a conversation that is ongoing.”

And while “Diet for a Small Planet” continues to be chock-full of research, charts, recipes and statistics, community is really what has always been at its center.

“I felt from the beginning that food had special power,” Frances Moore Lappé says. “It viscerally connects you to the earth and to people. I remember learning that the word ‘companion’ is rooted in the French word for bread, the idea of breaking bread with another person. What we eat, others notice.”

Frankie’s Feijoada

(Scott Suchman / For The Washington Post)

Frankie’s Feijoada

This vegetarian version of feijoada, a black bean stew, was a popular recipe in the original 1971 edition of “Diet for a Small Planet.” Later updated by a Brazilian friend of author Frances Moore Lappé with the addition of more vegetables and fresh herbs, it’s a hearty meal when served with rice and sauteed greens.

Makes 6 servings (8 cups)

2 tablespoons vegetable oil or another neutral oil

1 large yellow onion (about 12 ounces), chopped

1 green bell pepper, deseeded and chopped

1 medium tomato, chopped (about 1 cup)

2 cloves garlic, minced or finely grated

2 scallions, white and light green parts, chopped

3 cups cooked black beans or 2 (15-ounce) cans, drained

2 cups vegetable stock

1 small sweet potato (about 8 ounces), peeled and diced (optional)

2 stalks celery, chopped

1 bay leaf

1 ½ teaspoons table salt or fine sea salt

1 teaspoon finely ground black pepper

1 teaspoon white wine vinegar

½ teaspoon smoked paprika

Chopped fresh cilantro, for serving

1 orange, sliced, for serving

In a large pot over medium heat, heat the oil until shimmering. Add the onion, bell pepper, tomato, garlic and scallions and cook, stirring, until the onion is translucent, about 5 minutes. Add the beans, stock, sweet potato, celery, bay leaf, salt, pepper, vinegar and paprika and stir to combine. Bring to a boil, reduce the heat to low, cover and simmer for about 20 minutes or until slightly thickened.

Transfer 1 cup of the beans to a bowl and mash. Return the mashed beans to the pot and continue cooking, until the mixture thickens further, another 5 minutes. Remove from the heat, discard the bay leaf and top with the chopped cilantro and orange slices. Divide among bowls and serve right away.

Storage notes: Leftover feijoada can be refrigerated in an airtight container for up to 3 days.

Per serving (1 ⅓ cups), based on 6 servings: 232 calories, 5 g total fat, 1 g saturated fat, 0 mg cholesterol, 708 mg sodium, 38 g carbohydrates, 11 g dietary fiber, 7 g sugar, 10 g protein

Adapted from “Diet for a Small Planet, 50th anniversary edition” (Ballantine Books, 2021).

Hartke is a freelance writer, food stylist and recipe developer. This article appeared in The Washington Post.

Copyright: Special To The Washington Post